| CONTENTS | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | You Are Enslaved by False Information | 1 |

| 2 | Good Money – Good Life | 12 |

| 3 | The True Origin of Money: Mesopotamia 8000 BC | 14 |

| 4 | Here is the First Theory of Perfect Money | 30 |

| 5 | Economists are Wrong About Money | 40 |

| 6 | Economists are Wrong About Monetary Systems | 47 |

| 7 | The Big Myths of Money | 52 |

| 8 | The First Monetary Reference Model | 59 |

| 9 | Confidentiality: The Opposite of Surveillance | 69 |

| 10 | CBDCs: To Surveille or Not to Surveille | 76 |

| 11 | Monetary Availability | 85 |

| 12 | Monetary Integrity: The Opposite of Corruption | 98 |

| 13 | Monetary Preferential Integrity | 115 |

| 14 | The Real Reason Money Becomes Valuable | 123 |

| 15 | What Everyone Gets Wrong About Inflation | 131 |

| 16 | The Terrible Secrets of The Federal Reserve | 141 |

| 17 | Artificial Intelligence and Money | 150 |

| 18 | CloudCoin: An Experiment in Perfection | 157 |

| 19 | Perfect Money Platform Statement | 160 |

| 20 | This Author’s Journey | 164 |

This book will equip you with knowledge needed to refine your wealth-building strategy, fight your enslavement and help build a prosperous and free civilization.

The economist’s definition of money is thrown out. Monetary systems are in fact information systems designed to tell us who created value and who deserves to receive value. Learn how to spot monetary-system hacks and know what so-called “inflation” really is.

The economist’s definition of money is thrown out. Monetary systems are in fact information systems designed to tell us who created value and who deserves to receive value. Learn how to spot monetary-system hacks and know what so-called “inflation” really is.

Today’s monetary systems lack confidentiality, integrity and availability. The Federal Reserve Bank has been weaponized by Washington DC and is the single biggest threat to our liberty.

But here lies the solution that will undermine all authoritarian institutions in the world.Ten thousand years ago, in ancient Mesopotamia,a system of self-representing ceramic symbols was used to authenticate cash made from clay.

Questions that confounded economists, government officials, banking professionals, investors and even archaeologists will be answered. How much money should there be? Who should create money? How can we evaluate monetary systems? Can we have civilization without money? Where does money get its value from? Is there “Perfect Money”? And hundreds more.Money was not simply created one day but evolved over thousands of years.

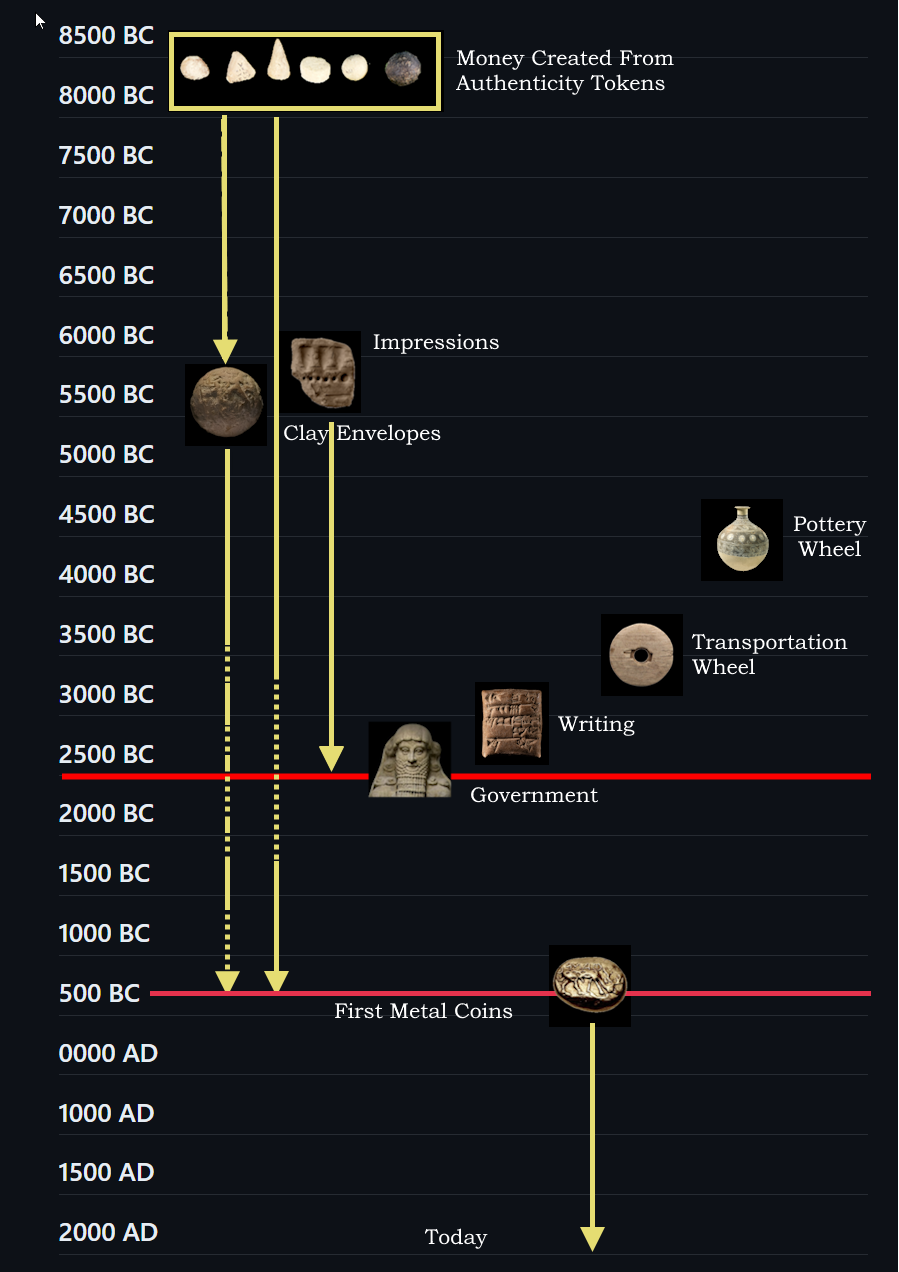

Ten thousand years ago, the last ice age was just ending. The ocean had just risen by 400 meters, swallowing up any coastal dwellings that may have existed. Areas that were dry before, such as Mesopotamia, suddenly became wet with rain. The people were still in the stone age and just learning how to farm. They hadn’t invented irrigation yet and scythes made out of copper would need to wait another three thousand years. There were no kings, governments, armies, numbers, or writing. However, they had just invented ceramics. Amazingly, there new ceramic technology was not at first used to make pots or vessels. Instead, ceramic technology was used to create geometric solid shapes. Keep in mind that pottery and ceramics are different. When thinking about ceramics, think about toilet bowls. The Mesopotamians fired clay geometrical shaped objects in their recently invented kilns at thousands of degrees Fahrenheit to convert them into a hard insoluble ceramic. What they created was data.

When tokens were invented, they were great novelties. They were the first clay objects of the Near East and the first to be fired into ceramic. Their shapes also were revolutionary since, as Cyril Smith has pointed out, they first exploited, systematically, all the basic geometric forms. ~Schmandt-Besserat pp 17

Archaeologists have called these objects tokens, counters or simply clay objects. These solid shapes include spheres, cubes, cones, disks, pyramids and more. To archaeologists, these shapes seemed to be symbols. Symbols that represented something else. Perhaps the cubes represented the number 5 while the spheres represented the number 9. Maybe one cone was one bushel of wheat while a pyramid was a goat. Or maybe they were just game tokens used in a game that didn’t use a game board. Keep in mind that the wheel and thus the pottery wheel wouldn’t be invented for another 4,000 years and writing would be in 5,000 years.

Plain Token: Token typical of the periods between 8000 and 4300 BC and after 3100 BC. The shapes are mostly restricted to cones, spheres, disks, cylinders, and tetrahedrons. ~Schmandt-Besserat pp 13

As a person with a PhD (ABD) in Computer Information Systems, I understood these tokens to be data. Data are symbols with meaning. However, this data was significant because the data is “self-symbolizing". Self-symbolizing means that a sphere symbolized a sphere, the cube symbolized a cube and a disk symbolized a disk. These symbols were quite beautiful and extremely advanced for stone-age people. How would they even know about these solid shapes?

This data was the most primitive that data could be because it didn’t mean anything besides itself. However, the use of ceramics to make the tokens gives us a clue to what they were used for. These tokens were high-tech items at the time. They would have been extremely difficult to counterfeit. Earthenware files at 1800 degrees while the tokens were probably fired at 2100 degree. Hotter than lava! That takes knowhow and resources that were not possessed by the typical person.

It is not at present possible to establish the meaning associated with each token type ~Artifacts of Cognition: The Use of Clay Tokens in a Neo-Assyrian Provincial Administration, John MacGinnis et al.

These solid shapes were not counters or symbols that represented sheep or bushels of grain. They were authenticity tokens and were used to stop the counterfeiting of rights to resources.

The catalog of seven thousand tokens has been compiled by studying the collections in the museums where they were stored~ Schmandt-Besserat pp 31

Looking at the context of where these authenticity tokens were found, it is clear to me that these geometric shapes were used to create the first locks and keys which would later evolve into the first money.

Back then, the first farmers had a real problem. They needed a place to store their grain where it was safe from barbarians, theft, fire, pests, and floods and other catastrophes that could ruin them. The answer was to store the grain in banks. These were buildings managed by priests and constructed from their newest technology: bricks. The problem was that the priests could not remember which farmer owned which grain. There was no writing at that time and they didn’t even know how to make scratch marks to represent numbers. They did not have symbols, let alone symbols for farmers and store rooms. If the priest forgot (or never learned) the relationship between the farmer and the storeroom, the farmer could lose access to his grain. And what if the priest died taking all the information with him? What they needed was authentication. They needed a way to authenticate the farmers without the use of writing.

The data available on the structures associated with tokens indicate that the ‘counters’ were often located in storage facilities and warehouses. ~ Schmandt-Besserat pp 97

Authentication can be achieved by having a shared secret between the farmers and the priests. If we think about modern day locks and keys, the key and the lock share a secret. The shape of the key is the same as the shape of the lock. The Mesopotamian were successful in creating the first locks and keys. These locks and keys were extremely primitive by today’s standards but very clever for people whose greatest technology was bricks.

To make their locks and keys, they would first need two containers (Data-stores). One to hold their key data (authenticity tokens) and the other to store the lock data. The lock data was probably contained in a bowl made from clay. This bowl would have been filled with sand and the tokens hidden under the sand. This bowl would have been located near the door or the storeroom. Most were found just inside the doorway.

The container for the key was probably a leather sack. To create a shared secret, the data in both the lock and key containers had to be the same. The priests would put the exact number and type of tokens in each container. The shapes they used were picked by random to thwart guessers.

Their distribution through the palace does not allow for any further conclusion as to their use or significance. All contexts in fact appear to be random, the tokens chance-finds - Artifacts of Cognition: The Use of Clay Tokens in a Neo-Assyrian Provincial Administration. John MacGinnis, M. Willis Monroe, Dirk Wicke, and Timothy Matney.

Again, the bowl would become the lock. These locks would be placed just inside of the doorways of storage rooms. The leather-bags with the matching tokens would be given to the farmer as the key. Now the problem of authenticating the owner of the grain has been solved. We assume that when the farmer (or anyone else with the key) shows up to access his grain, he gives his key (the sack of authenticity tokens) to the priest and shows the priest which storage room he owns. The priest then compares the contents of the farmer's leather sack to the contents of the bowl inside the storage room. If they match, the priest lets the farmer in. With this system, no one has to remember anything and there is no need to have writing technology.

No impression of textiles has ever been recorded, either on tokens or on the floor where they were recovered. It is more likely, therefore, that leather was preferred to cloth for storing the clay counters. ~ Schmandt-Besserat pp 97.

The system was also used at the gate houses of cities. People may have had to show keys in order to gain access to the city.

Eight buildings of Habuba Kaira, including one of the city gates, produced sixty clay counters, providing a unique insight into the distribution of tokens in the fourth-millennium Syrian city.~ Schmandt-Besserat pp 97.

The Mesopotamians may have also created a system that allowed the keys to include permissions. This would allow a key to be broken into parts and each part would give the user a different permission. Suppose you wanted to let your assistant go and count how much grain you have but you did not want to allow him to remove any. Or suppose you want your son to be able to remove grain but not change the key so that you would be locked out.

Permissions could have been implemented by making different shapes mean different permissions. The cylinders, for example, could represent the ability to see the grain. So, if a person wanted to just look at how much grain there was, they would only need to know the number of cylinders in the lock but would not need to know the correct number of cubes or other shapes.

The cones may have represented the remove permission that allowed the user to remove grain. If a person wanted to remove grain, they would not only need to know the number of cylinders but also the number of cones. The spheres may have allowed the user to change the lock. Changing the lock would require the user to have all the key parts including the spheres, cylinders and cones.

The permissions could have included: Inspect grain, Transfer to another room, remove a small amount, remove a large amount, add new grain, Change key, or Full control. There may have been special permissions like rearrange room and seal door. Actually, this is unlikely but it could have been done.

With this kind of permission system, there would be more keys that had full control as all keys would need to have that permission. Some people may have no interest in giving their key permissions so other tokens would be used less. So, we may see more spheres that are needed to grant full control than cylinders that are required for just read permissions because anyone with the spheres automatically gets read permissions.

Tokens, together with other status symbols, are sometimes included in the burials of prestigious individuals, suggesting that they were used by members of the elite. ~Schmandt-Besserat pp 107

Soon after, I think something interesting happened. Tokens began to be made out of highly polished stone instead of relatively inexpensive ceramics. I believe that the priests of the time figured out a way for them to get some extra grain from their followers. Like the indulgences of the Catholic church, the priest sold “Keys to Heaven." If you can create a key to a storage room, then why not create keys to other resources much more valuable, like to the doors of Paradise? The priest could sell these “heaven keys" at a high cost so that only the wealthiest could afford them. At these prices, priests would make them out of stone instead of clay to make them more valuable.

The manufacture of the plain clay token was simple. It required neither skill in craftsmanship nor complex technology. In fact, tokens could be shaped by anyone without the help of any tool. ~Schmandt-Besserat pp pp 30

I can imagine that the priest would attend the funeral of the person who died and pull out a jar (the lock) where he had long ago hidden random tokens in. He would take the key from the corpse. He would then break the jar open to reveal its contents. If there was a match, between the tokens in the jar and the tokens in the dead’s sack, he would declare that the person had entered heaven! If a jar was already broken, it was automatically labeled a fake - which probably never happened.

This system would allow a single family to buy a key and use it for the first family member who died. They could also sell the keys to others to creating a nonfungible token.

The next evolution of the Mesopotamian monetary system was the creation of spells designed to either summon demons or banish them. People would purchase sacks full of random tokens from the priests and then burn the sacks in their hearths. Burning would activate the key so that a portal could be opened. Humans made of water, demons made of fire, the demons would be expected to dwell in their element.

These keys to demon gates would be placed in special data-stores that were impossible to open without destroying the container. These containers were flammable and probably made out of basket material or pulp that was sealed by some kind of pitch, glue, or paint. The priests would want a pyrotechnic display when they were burnt.

It is puzzling that counters were located in fireplaces…One of these houses was still filled with long spouted jars that held a black, powdery substance. - Schmandt-Besserat pp 97

The reason I recognize this lock and key technology as the beginning of an ancient monetary system is because I, myself, have a patent on a modern version of this technology: USPTO #10,650,375 Method of Authenticating and Exchanging Virtual Currencies. I implemented this technology in a digital currency called CloudCoin. It is the World’s first digital cash.

Back then, if you didn’t work as a farmer then you probably worked as a priest. Priests would have been able to do all the work that farmers did not do, including being a doctor, therapist, magician, advisor, artist etc. There was not much to know about any of these subjects so it would have been easy to learn them all. The priests were able to create temples by rallying followers. They took on the role of being bankers by storing grain in the temple warehouses. There were over 3,000 gods back then so it was easy for priests to specialize and gain adherents. However, it is clear that there was no centralized religion and no governments. Kings would not arrive for another 3,000 years.

Priests would each create their own blessings to pay the workers who created their temples. These blessings were just keys that could be traded to others. They were pretty much exactly like locks only they were not backed by grain and did not open magical portals.

But the system still had a problem to overcome in order to be real money. The money that the priests made had to be counterfeit proof, otherwise it would lose its value. The Mesopotamians then faced the same problem that I faced when creating CloudCoin. How can we make money that is file-based/clay-based? Anyone can counterfeit by simply making thousands of copies of the file/clay. After much thought, I realized that it does not matter how many copies of a coin there are. What really matters is that the owner of the coin can only spend it once.

Suppose that I have a data-store (file). In that file are 25 passwords composed of sixteen random tokens (hexadecimal numbers similar to clay shapes). Because I have the file, I know the passwords. Whoever knows the passwords is the owner. If I give the file to you, then you know the passwords too. Whoever knows the passwords can take the file to the server nodes and authenticate them and then change the passwords. Now you have become the new owner because you are now the only one who knows the passwords.

Suppose that I have a data-store (leather pouch). In that pouch are up to 9 clay random tokens (data). Because I have the pouch, I know what the random tokens are. Whoever knows what the tokens are is the owner. If I give the pouch to you, then you know the tokens too. Whoever knows the tokens can take the pouch to the priests and authenticate it. The priest has a record of what is in the pouch. These are called impressed tables and he created them when he created the pouch. The priest will smash open the clay ball and compare it’s contents to his impressed table. If they match, the coin is authentic. The priest will then issue the new owner a new coin to replace the old.

Now these sacks of solid shapes were real money with integrity. There was another epochal invention here: impressed tablets. These tablets that priests used to record what symbols were associated with which money required a new technology: A very primitive writing system.

The more than 650 tablets were stored in10 jars in a room of the outer courtyard of the Assur Temple. Four of the jars were fairly well-preserved, and three carried an inscription naming the owners - or rather responsible officials - of those archives. ~Artifacts of Cognition: The Use of Clay Tokens in a Neo-Assyrian Provincial Administration, John MacGinnis, et all 2014, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 24

A writing system uses a set of symbols and rules to encode meaning. The priests came up with a way to encode their authenticity tokens (solid shapes). They could simply take a lump of wet clay and press the authenticity tokens into it so that the impressions of the tokens would be understood as the contents of the pouch. Although it is very primitive, this is technically writing because the symbols are no longer self-representing. While the solid shapes in the pouch were pure data, these impressions in clay could be understood to mean the solid shapes in the pouch. The impressed tablets were abstract symbols that meant real tokens.

If these assumptions are true, this would be the first form of writing. Since they had not invented a pencil or any other writing utensil, the information was written by pressing the key’s solid shapes into clay.

Note that the word signs used in the quote below is used to describe the impressions made by tokens:

The techniques for impressing signs on tablets were the same as those used for envelopes. For example, signs were still made by pressing tokens against the surface of the tablets. This is the case for Sb2313 of Susa, which bears three large wedges showing distinctly the entire outline of the cone used for impressing them. Furthermore, the signs corresponding to pinched spheres, ovoids, and triangles had to be impressed with tokens since no stylus could have assumed such shapes. ~ Schmandt-Besserat pp 136

These impressive tablets were probably created for security reasons. Tokens in bowls could be switched by corrupt guards so that counterfeiting was possible due to inside jobs. However, this problem could be solved if tokens could not be switched around and the tablets stored in jars whose lids could be sealed with clay in rooms whose doors could also be sealed with clay. These seals allowed the priests to detect tampering of the data.

It is remarkable that each of the 17 impressed signs can be traced to a token prototype. ~ Schmandt-Besserat pp 133

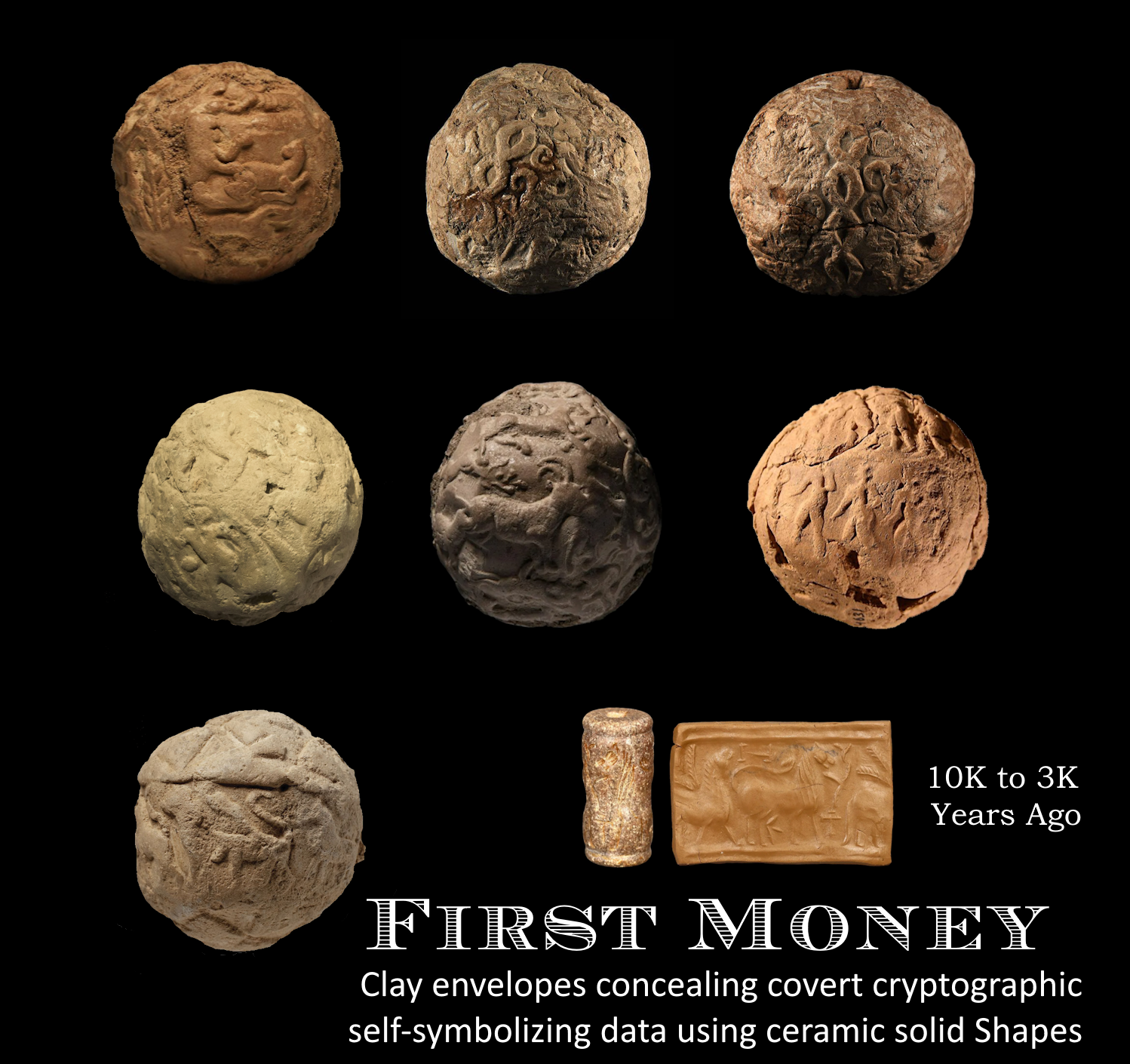

The next step in the evolution of Mesopotamian money was the invention of additional counterfeit prevention measures. This invention took another 5000 years to develop. To reduce counterfeiting, increase the people’s confidence in the currency, and reduce the number of counterfeit detections that the priests were required to do, they developed cryptography.

Instead of putting the authenticity tokens in leather pouches, they decided to hide authenticity tokens in 2-inch clay balls. They then rolled a cylinder seal on the outside of the clay ball before it dried. This seal would have been very difficult to counterfeit. Then they included the equivalent of a serial number to the outside so that the priests could find the matching tablet where the matching data was recorded. The purpose of the seal was also to show the user who the administrator was so they knew where to get it authenticated. The clay ball above was probably made by a priest who worshiped the god of the horses and lions. The ball is only two inches wide.

Cryptography is the process of hiding information so that only the person that it is intended for can see it. To achieve authentication, there needed to be a shared secret between the priests and the money (clay balls). The shared secret was the authenticity tokens inside. To keep the secret, priests hid the authenticity tokens by simply covering them in clay. This must have been one of the first cryptography methods known to.

To repeat, if a person was offered a mud ball as payment but suspected that the mud ball was counterfeit, both the buyer and the seller could go to the counterfeit detector (priest) and have the mud ball broken open to see if the tokens matched what was recorded on the administrator's tablet. If the mud ball was good, the administrator would then issue a new mud ball to the new owner.

This new mud ball would have a new and different combination of tokens hidden inside. This was very efficient because mud was cheap and the priests had the time. Because of the counterfeit protection measures already in effect, it was probably rare for the administrators to need to inspect the balls.

Thanks to this first money, humans for the first time came together to form a collaborative specialized workforce where jobs and professions existed for the first time. The first economy. The first civilization. The first free market and the first Capitalism. The money that was made out of simple clay. All this in a time when mammoths were still believed to walk the earth and three thousand years before the great pyramids were constructed.

The answer is Money. Money is required to enable more than one hundred people to organize a proper economy where people are dividing labor efficiently and productively without a dictator that owns everything. Civilization in Mesopotamia developed at the same time as their money which was created out of ceramic authenticity tokens. That was six thousand years before governments.